SERIO is a registry for adverse events of immunotherapies (immune-related adverse events, irAE).

In particular, we aim to collect cases of rare, complex and therapy-refractory adverse events as well as adverse events in special patient groups (i.e. patients with autoimmune diseases or patients with a solid organ transplant). Immunotherapies include checkpoint-inhibitors, cellular therapies, e.g. CAR T cells, and bispecific antibodies.

Our goal is to improve side effect management, gain insights into the pathogenesis of irAE, and be able to make predictions about irAE.

Who we are

SERIO is based at the Department of Dermatooncology at the University Hospital of Munich (LMU). The SERIO online register is operated in cooperation with the Paul Ehrlich Institute. Over the past 13 years, we have collected more than 1832 cases of rare, complex or very severe side effects from 27 centres in 6 countries. We cooperate with side effect specialists from all over the world.

SERIO was first initiated in 2011 by dermatooncologists from the University Hospital of Erlangen. The first documented case of SERIO dates back to 2009. A close collaboration with endocrinologists, cardiologists and gastroenterologists soon developed, which led to the initiation of our interdisciplinary Tox Board. Our cooperation with the Working Group Dermatooncolgy (ADO) includes the implementation of joint projects and the exchange of experiences.

SERIO aims to help physicians manage side effects and gain better knowledge of side effects induced by immunotherapy.

What we do

- Collect and analyze cases of rare, complex, severe and therapy-refractory adverse reactions induced by immunotherapy

- Provide physicians with recommendations for the management of irAE

- Conduct research and assist others conducting research related to irAE

1533 - irAEs 77 - centers 17 - tumor types

Case of the Month

44-year old female patient with pembrolizumab-induced polyserositis

10/21 superficial spreading melanoma (Breslow thickness: 1.5mm), localization: upper back

Axillary Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy left (1/1) and right (0/1), pT2a N1a M0, St. IIIB (AJCC 2017)

BRAF V600E

12/2021 – 09/2022 – adjuvant therapy with pembrolizumab (12 cycles)

11 months after initiation of immunotherapy with pembrolizumab, the patient presented with pleural effusion and ascites. First, steroid therapy was initiated. During steroid tapering, the patient developed recurrent chylous pleural effusion and ascites. Steroid therapy was re-initiated but without success. Spironolactone, antibiotics, and a fat-free diet were initiated. Steroid therapy was stopped. Subsequently, the patient presented with severe dyspnea and fever due to recurrent chylous pleural effusion and ascites. Repeatedly pleural effusions and ascites were drained yielding up to 5 liter of fluids with no evidence for malignant cells. Staging and assessment of the tumor marker S100 revealed no progression of disease. The young patient had to quit work and has been in and out of hospitals for 5 months. She also appeared cachectic upon our first consultation.

Since symptoms were steroid-refractory upon relapsing symptoms during steroid taper and the second increase of steroids we initiated systemic therapy intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG). After 4 cycles, we started parallel treatment with Extracorporeal Photopheresis (ECP). Lymphangiography was planned to rule out lymphatic fistulae. The patients` condition has significantly improved upon start of IVIG in combination with ECP. She currently reports no dyspnea, with less ascites. She adheres to a low-fat, high-protein diet. ECP and IVIG therapies are ongoing.

Therapy with ruxolitinib could be considered in the future. Follow-up nutritional and metabolic consultations are scheduled to evaluate the further approach regarding the fat-free diet.

The checkpoint inhibitor therapy was permanently discontinued.

The patient presents with a complex case of checkpoint-inhibitor induced polyserositis with recurrent chylous pleural effusions and ascites induced by adjuvant anti-PD1 therapy. The treatment approach has involved a combination of immunomodulatory and nutritional interventions in addition to repeated drainage of the effusions.

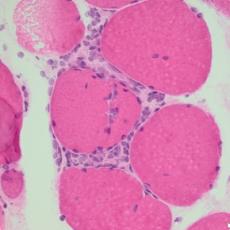

IrSerositis is a rare side effect of immunotherapy and can induce potentially life-threatening side effects with cardiac and pulmonary affection (Zierold et al., 2022). Knowledge about this immune-related adverse event is scarce. It can manifest acutely or progress slowly, occurring between 7 days and up to 72 or even 200 weeks after initiation of immunotherapy (Zierold et al., 2022). Concurrent malignant infiltrates are possible, emphasizing the importance of histopathological analysis (presence of lymphocytes, absence of malignant cells) (Zierold et al., 2022). Treatment of irSerositis can be challenging. High-dose steroid therapy could be a viable primary treatment option. Nevertheless, frequent pleural or ascites drainages are often required. For steroid-refractory immune-related adverse events (irAEs), a second-line therapy may be initiated (e.g., Infliximab, Ruxolitinib). Once, spontaneous resolution was reported (Kolla et Patel, 2016). Tumor outcomes during treatment of irSerositis vary (Zierold et al., 2022).

Polyserositis is a very rare side effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Prompt diagnosis with exclusion of malignant cause and treatment are essential. The patient's positive response to the current treatment regimen with IVIG and ECP is encouraging.